I read somewhere that we tend to memorialize and capture huge entrepreneurial successes – the blockbuster six sigma variety and there isn’t enough written about more achievable, realistic successes. The kinds of businesses that don’t normally grab headlines, don’t have splashy investors and fund-raises and thus don’t capture the public imagination as much. Taking that to heart, let me try and pen down some of my relatively contemporaneous thoughts capturing learnings from one such entrepreneurial journey while still relatively fresh in my mind.

To start with some background, my business partner, Anmol Bhandari and I founded Cians Analytics in 2009, some 12+ years ago. We recently sold the business to a private-equity backed competitor firm. I would describe the outcome as a successful one – we sold a growing and profitable business to our largest competitor in a deal of our choosing. Ours was not a capital-intensive business but the value creation in terms of investment returns were well over 50x, i.e. for every 1 Rupee that went into the business, more than 50 Rupees came out as return, in the aggregate. That still may not make this a business that a venture capital firm would like to fund (more on that later), but it certainly provided a high return to shareholders (including employees) who stayed with the business. Our employees and clients are now part of the #1 firm in the industry, so overall a satisfactory outcome. Other than Cians, I have also been part of a few other early-stage businesses and have been an angel investor (though not a very active one, given time constraints for the last several years) which gives me a different perspective from the other side of the table, as well.

As some of the learnings from my entrepreneurial journey and experience working with other early and growth-stage firms, here are some words of advice for entrepreneurs and potential entrepreneurs:

Have a focus on getting to profitability. Quickly

“Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen nineteen and six , result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery” ― Charles Dickens

In my experience, what worked best for us was a focus on achieving profitability as soon as practical. This mindset allowed us to be self-sustaining early on. After an initial 1-2 years (will depend on the capital intensity of the business you are in) where it would be difficult to achieve profitability, you should be able to get over the hump and strive for profitability. This allows you to grow in a way that, as founders, you want to grow rather than being driven by external investor views and needs. I am reminded of Russ Hanneman’s character in the terrific HBO series Silicon Valley (especially season 2) which I think while very tongue-in-cheek, is not far from the truth in the characterization of certain types of early-stage investors and the risks of being dependent on investor whims and fancies.

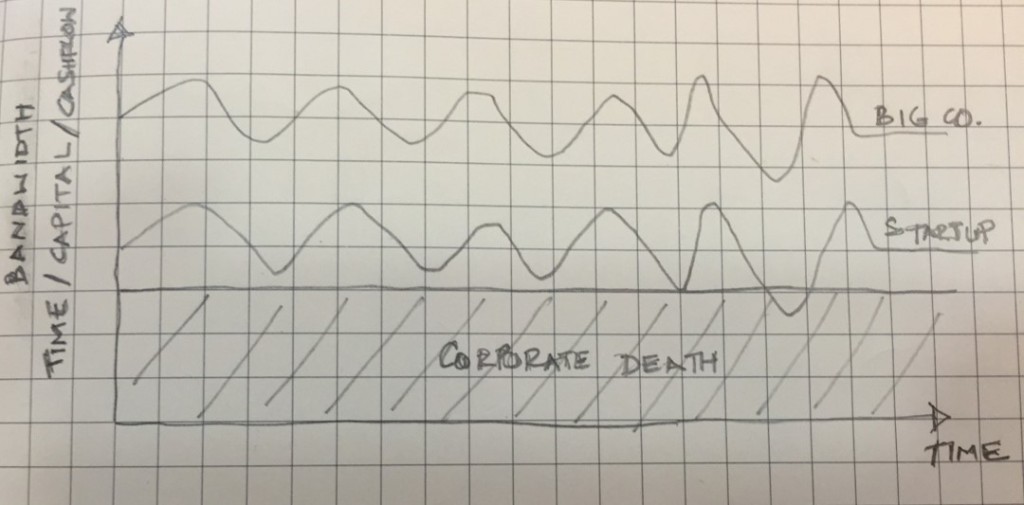

A lot of what one has seen globally, especially in startups covered by the press over the last few years has been a focus on investor-driven growth. VC firms or other early-stage institutional investors have invested in businesses and owing to their return expectations, have resulted in companies often focusing on growth at all costs. When the focus of a business becomes to show a step-up in growth and short-term performance with the primary purpose of using that performance as a way to justify raising the next funding round, that results in a business that has skewed priorities. Growth is a much higher priority than profitability, in this case. As a result, firms often achieve a reasonably high level of growth and scale but have often still not achieved profitability nor do they have line of sight on profitability (some frankly haven’t figured out what their business model is despite a fair amount of scale), and thus remain at the mercy of external capital. Given that external capital availability is cyclical, this can be very dangerous for a business if the capital cycle turns and liquidity becomes tight (as has happened since the second half of 2022).

In my view, the better approach is to focus on building a great, self-sufficient company. Investors and investment will follow.

Build for the customer. Not for the investor or anyone else

“Organizations are successful because of good implementation, not good business plans” – Guy Kawasaki

This is related to the above point but is an independent one. One part of this advice is exactly what it says – you need to tailor your product or service offerings towards meeting a customer’s need. That is paramount. Unless your customer is willing to take money from their pocket and put it into yours, you do not have a business. It doesn’t matter what investors say is hot, exciting, and a great opportunity. The north star for an entrepreneur has to be delivering something of value to a customer at a price that the customer is willing to pay. Customers have to choose your product or service over other competing alternatives.

The second point is that when you have external investors, especially investors with meaningful stakes in the company, you have to take their views and advice into account. This can often be useful as they provide a good sounding board for the founders to share their ideas, but depending on the structural arrangement (number of board seats held by investors, mindset of the investors, etc) sometimes this can result in a conflict wherein what the founders think makes sense and what the investor/s think makes sense, could be different. This can be for various reasons, including the fact that the VC investor business model is more of a home-run business rather than a singles and doubles business (to use a baseball analogy). VCs manage a portfolio of investments. They recognize that of the 100 investments they make, more than 50 will return close to nothing, and most of the value of their portfolio will be driven by a handful of successful investments (unicorns, decacorns, etc). This results in VC firms mostly focusing on business models that have high-fixed cost and more importantly low-variable costs – the typical businesses that are hit or miss. If you hit, you are stupendously successful since the business is highly scalable at low cost since there is low incremental cost once you get to a certain level of scale. If you miss, you are out of business. This also often makes investors keen to have their portfolio companies swing for the fences, and adopt a more risky strategy to try to achieve a superstar outcome. The risk of that is that if the strategy fails the company may end up bankrupt. The VC has 99 other investments to limit this risk even if one company goes under. The founder has only one.

Entrepreneurship to me: Stargazing, with your feet firmly on the ground

To me, running a startup requires very contradictory skillsets. That’s what makes it hard. You need to have a long-term vision with a reasonable idea of where you want to get. A goal, a destination, even if it’s a broad idea rather than a specific one. You need to have a sense for the macro picture, where you want to get and a broad vision for how to get there. What some call strategy. At the same time, you have to live in the present. You cannot take the eye off the ball from today’s problems, today’s issues — the micro. For small companies especially, you have to spend most of your time and energy handling the day-to-day minutiae and building on each small achievement so that you can have a shot at a very different tomorrow. You have to manage time and costs wisely, while also investing for the future. Often these two different perspectives pull you in different directions – for example, do you reduce prices to woo a client who is on the fence, or do you hold the line and keep prices consistent so that you can build your brand and not be known as a company that undercuts competitors. The answer is different depending on the time scale you choose – the short-term answer is often different than the long-term answer and in the end you have to balance the two.

The Capital Question. How much capital do you need. How much should you raise?

“Money is like gasoline during a road trip. You don’t want to run out of gas on your trip, but you’re not doing a tour of gas stations” – Tim O’Reilly

This is a very tricky question. As is often quoted (though it seems almost farcical), the number 1 reason startups shut down is because they run out of money. While this statement is obvious, it does speak to the fact that you really don’t want to get to a situation where you don’t have enough cash in the bank to keep the business running. The consequences of running out of money are terrible, so you don’t want to end up in that situation.

At the same time, my personal view is that I think the fact that having a very limited amount of capital actually helped us more than it hurt us, when I think about my experience. It made us think very hard about what we spent money on, it prevented us from doing some foolhardy things that seemed interesting at the time and would probably have been detrimental to the business. I look around and see many businesses that over the last 5-10 years have had too much access to capital because of the easy flow of money into startups, and a lot of them used that funding window and squandered a lot of money in the process. Having too much money in the bank can be a problem if not handled judiciously, as it could result in you running down every rabbit-hole that seems like a good idea at the time. When money is “free” almost every new project or investment opportunity seems justified and has the potential of covering your cost of capital (near zero).

My view on this in general is that capital is a means to an end. You want to raise capital so as to get you to a point where you have a self-sustaining business. To my mind, getting to that self-sustaining stage early on was of paramount importance. Once you get to the self-sustaining stage, and achieve escape velocity, you stop being dependent on external investors to keep you going. This is critical. Paul Graham of Y Combinator summed this up beautifully in his essay called Default Alive or Default Dead (http://www.paulgraham.com/aord.html) where he describes how a startup should strive to go from “default dead” to “default alive”, which marks a critical point in its startup journey.

From what one sees in the popular press, fund-raising is often viewed as an end in and of itself. While I do think that one should celebrate a fund-raise because it gives the startup the runway to try to deliver results, it is dangerous to start looking at fund-raising as a goal. To my mind, rather than it being a goal to achieve, it creates an obligation for the startup to use the money efficiently so as to generate a return on the capital. As a rough rule of thumb (exact math will depend on the cap structure, capital intensity, valuations to outside investors, etc), founders need to get the company valuation to be at least 10x the total amount of capital raised during the life of the company, for the investors to make a reasonable return. So, if you raise $1mm during the life of the company, you need to be worth at least $10mm at exit. Similarly, if you raise $100mm in capital, you need to be worth $1 billion at exit. If you don’t get there, the math will likely not work for the investors.

Sidenote: I sometimes meet founders who think one of two things. 1. It’s the investor’s job to make the business a success and to open doors and help get business. 2. They think investors are risk-jockeys who blindly put money into things (think free money) without requiring safeguards, restrictions, covenants to protect their investment, and line of sight on potential return. My view on both those items is No and No. Investors may help with #1 but you really shouldn’t expect it. A good investor stands by you and provides advice and counsel where needed, and lets a founder drive the train with the goal of generating returns. And an investor usually has a fiduciary responsibility to take steps to put conditions and a framework in place to protect their investor’s capital. In addition, investors always need line of sight on potential return. The most simplistic way to think about how investors calibrate opportunity: if the investor puts $100 in, she wants to know how many years later she will likely get an exit, what % of the company will she own at exit date (depends on how much future capital the company raises), and what will be the value of the Company at that exit date. The risk of her investment is captured by looking at the probability of achieving each of these – the likelihood of an exit, the likelihood of achieving that exit valuation, and the likelihood of retaining a certain % ownership.

Pay your taxes. Take compliance seriously. Honor your agreements

“The first thing is character, before money or anything else” – JP Morgan

“It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it. If you think about that, you’ll do things differently.” – Warren Buffett

This is true from both a legal and a practical standpoint. Rules and regulations can sometimes be tedious to monitor and implement in your business. But you must take it seriously. Apart from the obvious reasons to do this (it’s the right thing), this will also be critically important if you end up raising money from institutional investors, or if you are lucky enough to get to IPO or a strategic sale.

Wearing my investor hat, this is something I have seen as erratic with many companies and it can be a serious hurdle to external funding.

Growing up in a family where my mother and father both worked and paid their taxes, no questions asked. And were steadfast about following rules, I have always come at this from somewhat of a puritanical perspective but its really in a founder’s best interest to give this serious consideration. Spend the money to get good chartered account advice and a part-time company secretary. Hire a lawyer (I know its expensive and have not done this as often as I should have) as a one-time exercise to get clean contracts in place, and then for ongoing major events.

Having contracts in place is important (client contracts, employment contracts, etc) and you must spend time on them. At the same time, to be honest, I have had experiences where people have honored their word without a contract in place, and others who have reneged on contracts despite full legal contracts in place. I guess that’s part of life but one learns over time how to size up counterparties and assess the risk from different contracts/with different stakeholders. I believe there is an element of karma here though. If you are known as someone who honors your word, that helps both your conscience and your bank account, because people trust you and trust is very hard to build.

How do you track your business? How to keep the business on track

“What gets measured, gets done” – Tom Peters

The good part of having external investors and independent board members is that they often have the ability to keep you focused on metrics and achieving milestones. That comes naturally to a lot of professional investors and is something that a lot of founders don’t have as good a feel for. Whether you have external investors/board members or not, I think this is a discipline you must have. Set targets for the year and for longer periods, monitor progress against the targets. Maintain dashboards that provide feedback on how you are doing. As I am also an investor in some other early-stage businesses, I have often seen founders who are reluctant to put out targets for fear of not being able to achieve them. This is short-sighted since I believe you can never get to where you want to go, unless you have an idea where the destination is. Business is always dynamic and you may need to revisit the targets you set periodically, but that doesn’t mean you don’t go through the exercise.

I believe the same thing about things like financial projections. You have to go through the exercise of forecasting where you think the business is going to be at different times in the future. Going through this exercise allows you to identify and test the assumptions that are underlying the forecast. This is useful in and of itself and helps you understand the business better. It doesn’t matter whether the forecast ends up right or wrong (it will most likely be wrong), but it is useful to conduct the exercise. As George Box said, “All models are wrong. Some models are useful”.

Sidenote: if you plan to talk to any investor to raise funding, most will want this anyways.

Align incentives with as broad a group of key employees as possible. If using stock options, give a disproportionate number to folks who are likely to recognize what they are worth and thus could serve as both a hook and a meaningful liquidity event for the employee at some stage

“Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome” – Charlie Munger

I think it’s a great idea to make as large a group of employees participate in the company as investors, as possible. This aligns incentives between the employees and the shareholders. It also keeps employees motivated and has a positive impact on employee retention. If the company does well, everyone wins. There are clearly constraints to doing this, though. If you have a private company that has unlisted shares, the people receiving shares/stock options need to have the information to be able to think of them as having value. For most organizations, as you get to more junior folks, they are not privy to the information that will allow them to evaluate whether the stock options have any value and if so, how much. Thus, they are often wasted if you spread the stock options too thin. They are not meaningful enough for people to really think they will impact their lives, and thus don’t have the desired result.

Especially in a service business, you are only as good as the quality of your employees. But does that make employees family?

“Train people well enough so that they can leave, treat them well enough so that they don’t want to” – Richard Branson

This is a controversial question, and one that is very topical since several large firms and well-funded startups are now laying off large numbers of employees. This is at many firms that were considered very employee-friendly which were famous for pampering employees in the past. I think that each firm and the founders need to introspect on how they think about this issue, and then once they decide, they should be consistent in how they behave. There seems little point of firms offering free massages in the office and a host of other perks to employees in the good times and position themselves as employers of choice, only to lay employees off when times are not as good. Every firm has to weather the storms that they encounter and belt-tightening is a part of managing business cycles but I think its important to maintain some consistency in how you deal with employees, and to walk the talk when times get tough. From my perspective, I personally think its better to more cautious while staffing up as well so that you can carry employee costs when things are not as good. Additionally, I find it horrific how firms have chosen to conduct layoffs – some letting people go through group zoom/MS Teams calls, without even a one-on-one meeting. Other firms, just shutting off access to company systems and laptops without warning. Even if you have to conduct layoffs, I can’t imagine too many reasons why a company would need to do things this way. Thankfully, I have not been in a situation in my various roles as an entrepreneur or a senior manager, where I have had to let too many people go. Even when we did, there was no question that if someone was being let go or managed out, it would be through a one-on-one meeting with their manager. Managers must at least look an employee in the eyes, and have this unfortunate conversation if they find themselves in this situation.

On the broader point, while I like the idea of thinking of employees as family, I think the more appropriate way to think about it is what is described by Reed Hastings at Netflix. In his book, No Rules Rules, where Reed Hastings described his approach, he states that he believes the way to think about the employer-employee relationship is that of a professional sports player has with a professional sports team. There is camaraderie within a sports team. Players have loyalty to the team and to their team-mates. And the team, has loyalty to the players, and works to ensure the camaraderie stays. But the team manager’s job is to put the best team on the field on any given day, and each player needs to strive to do their best and deliver value. In the end, the team manager can swap out players or trade a player to another team. And the player can also choose to go and play for another team. Its only through creating an environment that fosters a mutually beneficial relationship that both sides stay satisfied and both parties grow and develop.

Strap In. Its going to be a long ride

“The only place success comes before work is in the dictionary” – Vince Lombardi

There are no overnight successes (or at least very few). It usually takes 10+ years to get a business to a stage where you can monetize the business (IPO, M&A) since that’s often how long it takes to build a sustainable business. The first few years of a startup are incredibly hard.

An entrepreneurial journey is almost never a straight upward line, even in the most successful businesses. Most startups struggle for money at some point. Most founders end up in a situations where they have had to put in more money of their own to meet payroll, not take salaries for periods of time, and have had to ask some of their employees to take delayed salaries (I have had to do all three, at different points).

Building a company is a long journey and a lonely one. It helps to have a co-founder for many reasons but for that one too. You can bolster each other on your low days, when one is despondent the other could be upbeat and vice versa. It also helps to have a supportive spouse and family. My wife, Shravani, has certainly been one.

Final thoughts

The perception of entrepreneurship has evolved over the years. 20 years ago, a retail entrepreneur would derisively be referred to as a “dukaandar”. Today, we deify startups and entrepreneurship, especially those that are addressing large target markets. The press is filled with articles on decacorns, unicorns and soonicorns. We have gone from vilifying entrepreneurs to idolizing them. I believe we need to tone down both extreme views. As in most cases, the truth lies somewhere in the middle.

What enterpreneurship doesn’t provide is a get rich quick scheme. What it does provide is an opportunity for the founders to drive their own destiny.

What it doesn’t provide is a certainty of success or consistency of a paycheck. What it does provide is a way for you to test fate (so much of your outcomes are still determined by luck), your skills and strategy to compete against firms regardless of their size.

What it doesn’t allow you to do is to be a specialist (you are the person who has to solve the issues and problems that are not assigned to anyone else). What it does provide is a opportunity to be an all-purpose generalist.

What it doesn’t provide you is anywhere for you to hide when anything goes wrong since you are ultimately responsible for success and for failure. What it does provide is an opportunity to try your hand at fixing all the problems you see in a marketplace or in a work environment (coming from every job environment you didn’t like or every boss you disliked).

What it doesn’t provide is the compulsion for you to have a boss give you a performance evaluation or an appraisal. What it does provide though is an opportunity to be appraised by customers, employees and investors to deliver value to them. It is only by doing that, that you can try to attain business success.

In the end, entrepreneurship is a journey and not a destination. If you fight hard, and the chips fall in your favor, you can achieve a high (sometimes astounding) degree of success and wealth. If things don’t work out, you live to fight another day. In either event, you have to learn to enjoy the journey. As Christopher Morley aptly said, “There is only one success – to be able to spend life in your own way”.

Aman Chowdhury, February 2023